Valve Repair/Replacement

Heart valve surgery has a history dating back more than 60 years and during this time surgical techniques and types of artificial heart valve (known as valve prostheses) have been refined such that with appropriate patient selection, excellent long term outcomes can be reliably achieved. With the ageing of the general population we are seeing an increase in the number of older patients developing valvular heart disease, and if a heart valve becomes narrowed or leaky to the point where it is putting strain on the heart then a new valve, or repair of the existing valve, might be required. Conventional treatment is with open heart surgery, although percutaneous “keyhole” treatments, such as TAVI (transcatheter aortic valve implantation) and the MitraClip have an ever increasing role to play.

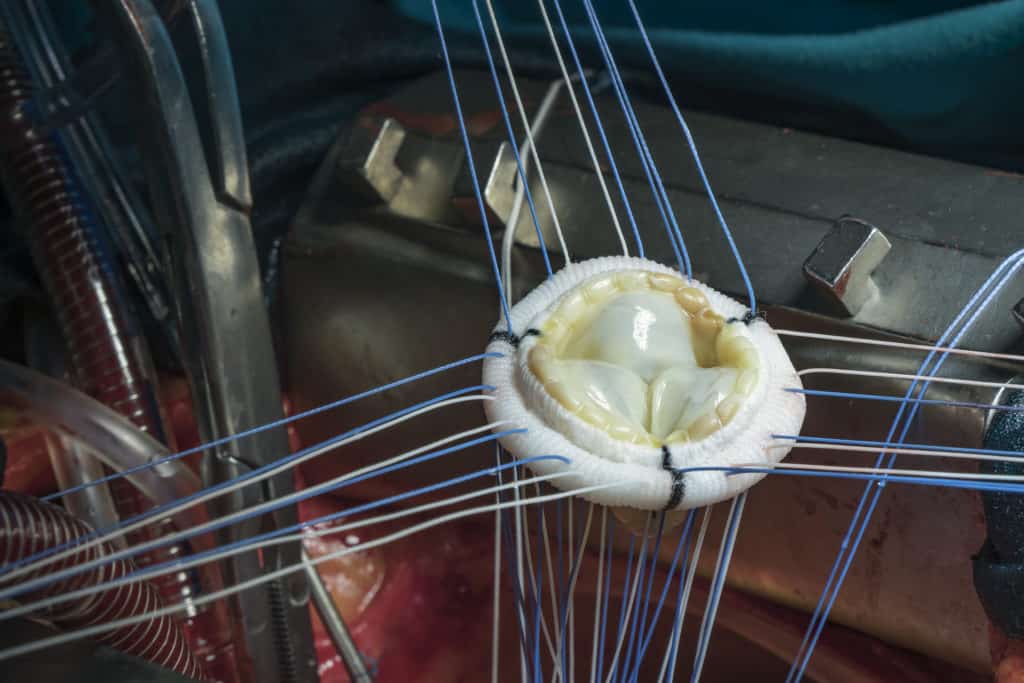

There are two broad categories of prosthetic valve, biological (also called tissue or bioprosthetic – as pictured in the image to the right) and mechanical (metal). Patients with a mechanical valve will need to take an oral anticoagulant, such as warfarin, for life to prevent clots forming on the valve which may break off into the circulation and cause a stroke. Bioprosthetic valves are typically made from pig, cow or human donors; they do not have the same tendency to form clots and so warfarin is not generally required. Mechanical valves tend to last longer than bioprosthetic valves, particularly in younger patients, but many other technical factors influence the choice of valve prosthesis; this is an important decision and should be discussed thoroughly with a surgeon so that the pros and cons of each particular prosthesis are fully understood.

Valve surgery is undertaken in a similar way to bypass surgery and involves a heart-lung bypass machine. Traditionally an incision, known as a median sternotomy, is made vertically through the breast bone, although more recent techniques using minimal access with far smaller incisions are undertaken more and more. The heart is opened to explore the damaged valve, which is then removed and a new valve sewn in its place.

The patient should expect to be in hospital for 7 days after the operation, occasionally longer. Some patients may require a permanent pacemaker in the early days after an operation; more so in cases of aortic stenosis, since the chalky deposits within the valve can extend into the adjacent electrical pathways of the heart and disrupt normal rhythm. To an extent the need for a permanent pacemaker can be predicted pre-operatively and patients will be counselled about their individual risk.

After surgery the patient should expect to be followed up regularly for life by a cardiologist to check on the function of the valve, together with the other heart valves, and to ensure that the most appropriate medication is being used to optimise their health in the long term.

Related links:

Symptoms - Breathlessness and Fluid

Retention

Breathlessness, or dyspnoea, is a common symptom of several medical disorders. Read more

Tests - Echocardiography

Echocardiography is the study of the heart using ultrasound. Similar to a scan of a baby undertaken during pregnancy, an ultrasound probe applied to the chest wall can be used to study the heart. Read more

Conditions - Valve Disease

The four chambers of the heart are separated by one-way valves to ensure efficient forward flow of blood from chamber to chamber and into the main blood vessels, the aorta and pulmonary artery. Read more

Treatments - TAVI

With the ageing of the general population in Western society we are seeing an ever increasing number of older patients, typically in their 70s, 80s or older, with wear and tear of the main heart valve, the aortic valve. Read more

Treatments - MitraClip

The mitral valve is a highly complex structure, comprising two leaflets, which acts like a one-way valve between two chambers, the left atrium and left ventricle. Read more